Class 13 Valuation: More on stories & first valuation

Theranos, Wework & Oompa Loompa of unlimited chocolates from nowhere...

Let’s assume the following company’s parameters:

CAGR of 50% in revenue growth for next 10 years

Operating margin of 20% in year 10, twice the industry average

Low reinvestment rate

Cost of capital of 7% in year 10

What’s the story as told implicitly above?

That the company is:

Small or large in size

Market size is growing or shrinking/stable

Strong or weak competitive advantage

A low or high capital intense business

Discretionary or non-discretionary product

When you are having a problem with someone’s valuation, it shouldn’t be about the numbers because you are playing on their turf. You have lost the plot when you ask why is 50% growth & not 40% growth, etc.

Every valuation has a story & most of the time is implicit as above.

Rather than reverse engineer the story from numbers, it should be framing the story first.

The story is something that we have to keep reminding ourselves of in reality-checking our valuation.

The story changes too, due to the following:

New information from the earnings reports, or from competitors’ earnings report

Macroeconomic

Regulatory or policy changes

In summary, (intrinsic) valuation is not fixed & is constantly changing.

There are more valuation changes in startups than in mature companies. This means you need a lot more stories on startups with fewer numbers, than on mature companies that rely on more numbers (& less stories).

// begin Class 13

To recap on the previous class on Impossible, Implausible & Improbable.

Impossible business are businesses with >100% profit margin, or growth that are higher than the economy in perpetuity.

Implausible business are businesses with high growth without re-investment, or returns without risk. It is plausible actually but there better be a solid explanation, for e.g. concession or licensing requirements.

The valuation triangle states the improbable relationship between Growth, Risk & Reinvestment.

High growth, high reinvestment & high risk. Or Low growth, low reinvestment & low risk. Both of these situations are internally consistent.

What’s internally not consistent would-be high growth but low risk or low re-investment, etc as described in the Improbable triangle above.

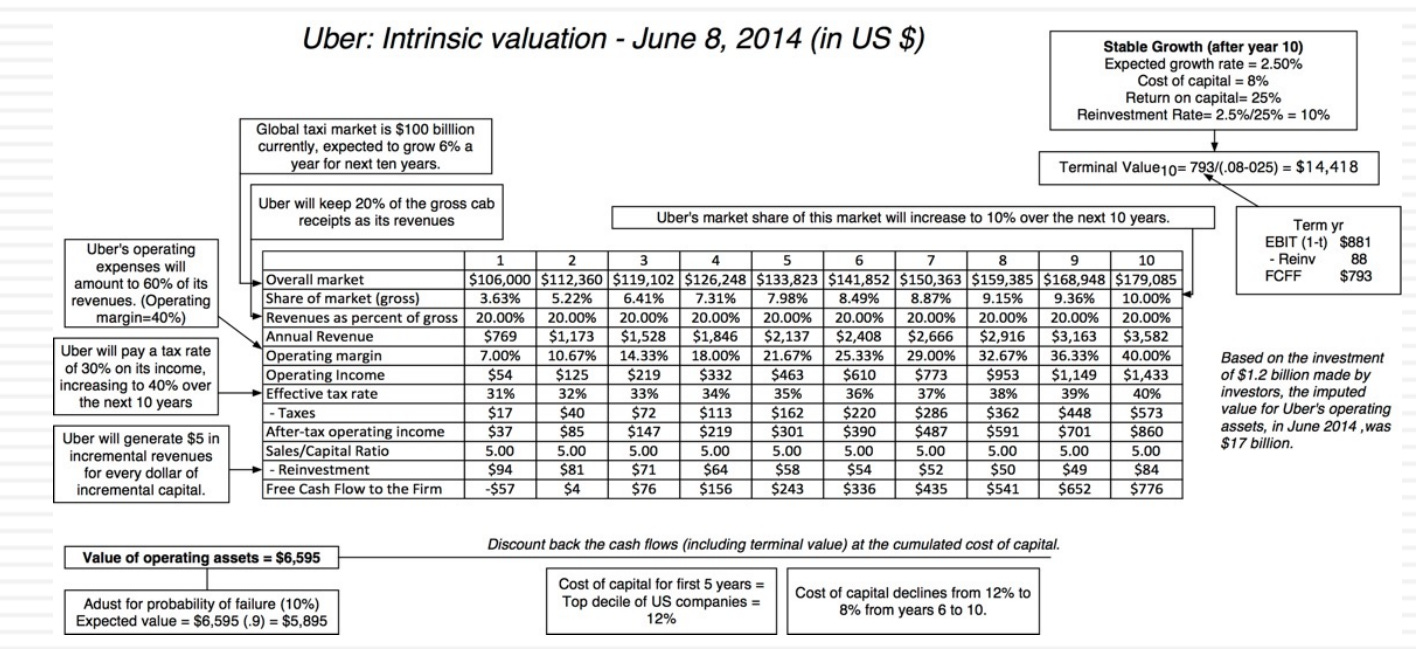

As Prof defends his earlier Uber valuation in June 2014, his first most logical step is valuing the “Probable” outcome, that Uber is only an urban taxi service provider. Then prof goes on with the “Plausible” outcome which is what Uber has achieved too, post-mortem. Everything at this point is defensible, a balance of both narrative & numbers.

Can the story be bigger?

Of course, as any founders would always do since they don’t need to do the valuation.

Tesla as a robot company? Sure, but please have numbers to back it up! What kind of robot? For what use cases? By when?

The moment you stop asking questions, this is where stories can fly — let’s visit some ingredients on how to make a good runaway story:

The story is told by a charismatic storyteller. You root for them & want them to succeed.

A story told about disrupting the status quo that is dissatisfied by everyone.

For a better society (i.e. altruism) if the story comes true!

Using an example:

A 19 y.o. who drops out of Stanford to start a software business. Is not he, but she. Unlike any other software company, but a blood test software company.

Nobody likes the blood test experience, right? What if everything can be done in just a single blood drop instead of a syringe full? No more waiting in hospitals too as you can do it at any grocery marts.

Do you want this story to be real? You want to. It was & is called Theranos, valued at $10 billion at its peak.

If you were to first value this company back then without knowing it was a fraud, what would be your first question?

“Does it work?”

It wasn’t asked until a WSJ article was published with the question answered - “it doesn’t”.

The lesson learned from such a runaway story is that it is very hard to ask the right questions when everyone around wants it to be true. Re-read the story of lemmings from our Class 2 below.

Class 2 Valuation: Bias, Uncertainty & Complexity

Story of the lemmings Prof. Aswath Damodaran does valuation to fight the lemmings. In a 1958 documentary titled The White Wilderness, a large group of lemmings are found to be mass migrating and appeared to be jumping off a cliff into the Arctic Ocean a…

Prof has written a very good account of Theranos in his blog.

Same with WeWork, when Masayoshi Son invested in Adam Neumann, everyone else stopped asking questions, esp. when Masayoshi threw in the numbers on why he thinks WeWork is worth that much.

We ask questions not to stop ideas & innovations, but to ensure the risks we are taking have basis.

Some good blog posts by prof on Wework too:

Author’s note: there are some who attributes premium of Wework was due to Adam Neumann himself. Remove him & Wework is nothing but a real estate company as many would think so. A more recent development is between Sam Altman & OpenAI that clearly proves this. Remove Sam Altman from OpenAI, the company has very little value left. I asked in my LinkedIn, is Sam the protagonist, or the antagonist in this whole saga as a intro on Prof’s corporate finance class on who actually controls the company.

The TAM / Big Market Delusion

To illustrate this point. Imagine an entrepreneur that is very bullish about his market and is also supported by VCs that share the same optimism. Each one of them wants to conquer the market.

Now sum this by the total number of startups out there in the same category. Assuming a market size of $100m & there’s 10 entrepreneurs out there. If each think the same of being a monopoly & own the entire market hypothetically, does it mean the market is not $100m x 10? It doesn’t make sense but in reality, each entrepreneur thinks he is the 1 to own the market.

Using listed companies as an example in 2015, the total market cap of the selected tech companies is $1.2 trillion globally, generating only $146 billions of revenues. This implies an almost 10x revenue multiple, showing the overvaluation of this space. What’s hypothetical is thus manifested in this overvaluation - a bubble.

P.S. NVIDIA is currently trading at >20x revenue multiple.

As long as there’s the next big thing, there will always be an overestimation of potential. For e.g. on the PC industry in 80s, everyone wants to start a PC company. Same with dotcom (that says will change life), EVs (that says will change life) and now AIs (that says will change life, but 3rd time a charm?).

Prof. gave the example of a conversation he had with someone from Singapore that wanted to improve the Singapore market with more trading & activity as it is currently muted. Prof. replied that this is possible, but it must also be prepared to have bubble that will crash. Then this person replied, “oh no, we don’t want that”.

Bubble & crash are features of the market, not a bug.

Tesla’s valuation in 2013

Prof first valued Tesla in 2013. As a side note, he highlighted that equity research analysts just chases the price. If the price is rising, equity analyst will recommend a buy. If it’s falling, a sell.

Being in the middle, not a Tesla bull or hater, prof came up with a value of $150/share. A famous equity analyst back then put out a big buy with a price target of $600/share. Prof gets curious, what did he see that prof misses?

In the analyst’s DCF assumption, revenue growth is in fact lower than prof’s. Margins are also in-line with prof. The problem lies in re-investment, where the analyst assumed very low re-investment!

This is like a Willy Wonka situation, where unlimited number of chocolates are produced by the Oompa Loompas out of a single factory.

Growth comes with re-investment! You cannot produce stuffs without putting money back in.

Back to the Uber Narrative

Each component of the narrative can be converted into a number.

Urban car service market ~ means global taxi/limo market. The leg work on this is heavy and to be as accurate as possible. Prof actually looked up each cities’ (about 50 in total) taxi regulator to look for the reported annual sales - at $50 billion. Prof then doubled it & called it “Global Market” instead of “US Market”.

The growth rate was actually 1.5% p.a. for the past 5 years but prof gave it a 6% p.a. projection due to new users’ acquisitions.

On 12% Cost of Capital - it was not built up like the previous classes. However, it was based on the 90th percentile of listed company’s cost of capital for the year. Meaning, the highest cost of capital compared to the other 90% companies. Failure rate is low despite it being a young startup because VCs are already pricing it at $17 billion.

From narrative to numbers, a valuation is born:

As a sense check:

Why is Uber having a $3.6 billion revenue in Year 10? Because Uber is an urban car service company with local network effect globally that can attract new users.

Why is the margin so high at 40% by Year 10? Because it is an intermediary company with low fixed costs.

Why is the reinvestment so low? Because it doesn’t produce or own cars.

It is important that this is Prof’s story, hence prof’s numbers.

The valuation for Uber back then as done by Prof was $6 billion, when VCs are pricing it at $17 billion. When asked why the big difference. Prof answered: I don’t know, I didn’t pay it, it’s not my money (on the $17 billion valuation)

If someone wants to pay $50k for Bitcoin, let them pay. Not my business, not my money.

Prof’s story, prof’s numbers, he wouldn’t pay Uber for $17 billion.

Your number, your value. This is how it will drive your investment decision. Problem comes when we outsource valuation. Or worse, outsource the decision making to experts.

Prof’s valuation was picked up by 4 different websites of various readership variety. These republications provided crowdsourced feedback to prof that is not a “ride sharing specialist” via the various comments (good & bad).

1 of the comments was: “How dare you value us (tech companies) via DCF?”

But Prof did learn a lot about the networking effect of Uber & the intense competition between Lyft & Uber with the various incentive schemes to attract drivers (pulling down margins). He subsequently updated his valuation based on these feedback received.

He also received an e-mail from Bill Gurley, a VC from Benchmark Capital & early investor in Uber with a $1 billion valuation, on why Prof grossly undervalued Uber. The email also linked to Bill’s blog post to counter prof’s valuation.

Some counter argument by Bill, that Uber:

Is not a car service company but a logistics company

Is not just in urban but everywhere

Connecting to airline via a seamless air-to-land service

etc…

Prof reacted by putting the above narrative back into his valuation.

A modified version of Bill' Gurley’s narrative land on a $28.7 billion valuation for Uber. Almost 5x of prof’s original valuation.

In fact, just to satisfy all the Uber bulls and bears, prof ran a simulation as per below:

Highest valuation on Uber back in December 2014 was $90.46 billion. Today, in February 2024, almost 10 years later & post pandemic, it’s at $145 billion, all time high.

In young companies, there are many versions of stories. It can also have high probability of breaking. Always look for things that would shift the narrative & thus the valuation.

Just on equity risk premium, economic changes mean the ERP rate changes:

First Valuation

Finally, after the groundwork, is time for us to start valuing.

With each company, the story starts first. Then to zoom into a specific component of the valuation.

First, let’s look into Consolidated Edison or ConEd. The power company for New York City, i.e. a regulated utility. Meaning a stable growth dividend model that can be used to value ConEd.

A litmus test to check:

Is the company having high dividend payout ratio? Yes, for ConEd with >70% payout ratio

Is this not a high-growth company but rather stable growth? ConEd’s retention ratio is 27% with a ROE of 7.7%. A product of these 2 numbers gives an expected (sustainable) growth of 2.1%. Lower than Rfr of ~4%. So yes, this is a stable growth company.

Next, would the cost of equity consistent with a stable growth company? At 7.7% Ke, which is the same as ROE. This looks OK, esp if in the regulated industry, the rationale to increase prices would be determined by ROE not exceeding Ke.

Next, to value using dividend discount model would be using the most recent dividend of $2.32, growing at 2.1%, giving an expected dividend next year.

Dividing the above with the difference of cost of equity 7.7% with perpetual growth rate of 2.1%, would give a value per share of $42.3. The price was trading at $40.76 in that period.

Thinking like a research analyst, what’s the target price 1 year from now? You factor in expected return & net of the expected dividend:

$42.3 x (1+7.7% Ke) - (2.32*(1+2.1%) Expected Dividend) = $43.18

It can go on for Year 2, Year 3, etc. Pretty impressive you can demonstrate this for an interview.

If the valuation is right, the price of today will correct up to $43.18, from $40.76. Hence, have confident with your valuation.

A summary of the above in below slide:

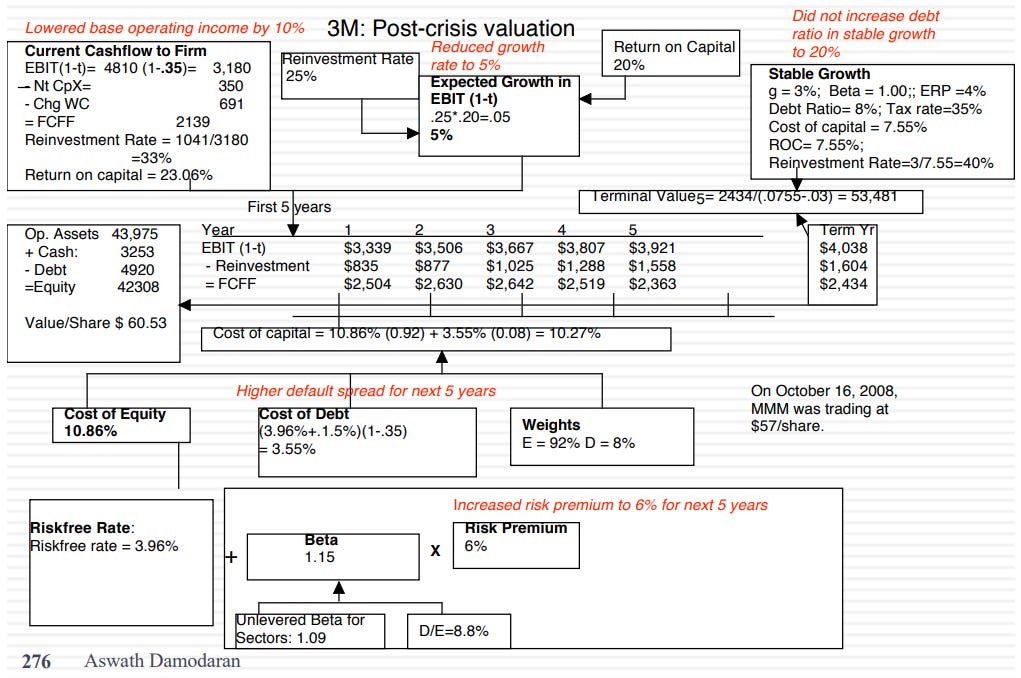

Next, 3M, an extremely boring company that makes a lot of money. Prof valued 3M in Sep 2008, a significant date that preludes the Great Financial Crisis.

$83.55 was the value/share, pre-crisis. In just a matter of a weekend, Lehman filed for bankruptcy.

Hence, Prof re-do the valuation with a few following changes:

Risk premium jumped which leads to higher default spread & cost of capital

Operating income & growth rate also reduce as there will certainly be lower sales & demand

Hence, a good practice is to separate all these assumption & levers in a separate sheet for fast reaction to any changes.

A crisis doesn’t mean there’s no value, but just lower value. In fact, it is the best time to practice valuation & use valuation as a form of sense check on bad news driven narrative.

Next class we’ll learn more about valuing young companies.

// end of Class 13 Valuation

Footnote:

Class video

Class slides

Tesla’s 2013 valuation spreadsheet from prof