A continuation from last class - the end game in business. Disney’s board was a rubber-stamp board & the CEO ran the company like is his.

So, who has the power in a company? Is it the shareholders, or the managers?

In reality, power can be from the lender, or the government (via golden share) too. How much power does a shareholder have to institute change? The role of the board is supposed to represent shareholders, but do they?

Good news is independence & governance in the board has been growing, ever since the introduction of Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002; enacted as a result of corporate fraud scandals from Enron & Worldcom.

There are even scores & ranking now to check corporate governance but at the end of the day, it’s just another checklist to fulfil though and sometimes even this is abused.

The only way to see if a board is effective is through their actions, i.e. a board stopping a CEO decision on an acquisition or decision on entering/leaving a market.

What happens when shareholders don’t have power?

If managers are not afraid of shareholders, they are going to put their interest up first & dress it up as “for shareholders’ interest”. Like a mouse will play when the cat is idle. Mechanism that managers will use to put their own interests above shareholders are:

Greenmail - Early 80s, oil companies were targeted by activist investors coming out of late 70s where the oil price boom caused huge amount of cash sitting in their balance sheet.

Unoncal, an oil company in California was targeted by T. Boones Pickens with a 5% shareholding accumulated (which would require a SEC announcement). If you were the CEO/manager in Unoncal, you were having a good life.

You find out 1 day T. Boones Pickens was offering a 20% premium of the share price to acquire the company, which option would you choose? Do your best to negotiate and maximise the premium for shareholders benefits, or to keep your day job & reject the deal?

Instead, you go to T. Boones Pickens and offered him twice the amount of what he paid to accumulate the 5% stake. In return, he has to sign a Standstill Agreement, agreeing that he will not accumulate more than 5% again. This is Greenmail.

Golden Parachute - same scenario as above but instead of offering to buy the acquirer’s share, you change the constitution of the company or your employment contract that allows a big compensation should there be an acquisition. Marissa Mayer of Yahoo got a $23m golden parachute & $184m payout in total. That money could be saved for minority shareholders in Yahoo.

Poison Pills - You don’t want to be acquired. So, you do something in your own company to fend of acquirers, by deploying a Poison Pill. Law firms will go to target companies and provide them this service of ensuring acquisition won’t happen.

Martin Lipton is a legendary lawyer on this - he created Shareholders Rights Plan, which was deemed as the most important innovation in corporate law.

A normal rights issue allows existing shareholders to buy new shares at a cheaper price, allowing companies to raise new money. But there’s a certain rights issue that allows you to buy new shares for a very high price. This will do nothing since it won’t be triggered, as long as you still run the show. However, if there’s a new acquirer, the rights issue price will drop to a very low price, allowing existing shareholders to acquire new shares at that very low price. This makes the acquirer needing more than just 51% of share to take effective control & hence needed more capital to counter the dilution caused by the rights issuance. This is the Flipover Rights Plan.

Shark Repellents - clauses you put in your corporate charter to make it harder to be acquired. For e.g. a normal threshold for takeover is 51%, you can change the charter to make it 67%. Another example is the staggered term of director’s renewal so that you can’t replace the entire board even if you have acquired 51% and taken shareholding control.

Overpaying on takeovers - If you are a manager of the acquirer, you should be minimising the acquisition price of a target or not trying to gather assets and build an empire for no reasons.

Manager will usually say: “We know more about this deal, trust us.” But if you look at the acquirer’s stock price, they usually drop in a takeover situation. Market/Investors says otherwise.

Synergy doesn’t exist, McKinsey has done this study multiple times over the past 25 years. Google “Mckinsey synergy studies”. The profitability of the combined firm actually decreases compared to the 2 individual firms before the merger. Half of the merger exercise got reverse within a decade after doing the deal.

Once company start to grow via acquisition, it becomes addictive because doing projects organically seems long & tedious. Might as well just acquire to grow.

Acquisitions in aggregate is actually more value destructing in all corporate actions put together. You can wipe out 20 years of hard work in just 1 bad acquisition.

Kodak & drugs

In late 1987, Eastman Kodak growth is declining & they got consulted to go into pharma because it was a growing industry. Firstly, where’s the synergy between camera films & drugs? Kodak then entered into a bidding war with Hoffman La Roche (a Swiss Pharma) to buy Sterling Drug.

The bidding war starts at $40/share, which increases to $89.50/share eventually when Kodak successfully acquired Sterling Drug. If acquisition is value destructing to begin with, the bidding war made it worse!

The day the bidding ends, Kodak market cap drop by $2.2 billion in 1 day, essentially means Kodak overpaid by $2.2 billion (total deal amount was $5 billion). Over the next 5 years, earnings of combined entity actually didn’t grow but declined.

Rumors that start to appear that Kodak wanted to exit the pharma business after 5 years which they denied. Few months later, the sale indeed happened at $1.7 billion, essentially a loss of ~$3.3 billion for Kodak - value destruction!

Bottomline: Managers will always put their interests first, there are times where the interests with shareholders converged. If there’s divergence, managers’ interest always win.

How do we assess where the power lies?

There can be 2 class of shareholders. Inside shareholders that are part of management, and they are outside shareholders who are not. If you are a shareholder in Adani Group, you will not have influence or control since there is a big block of shares held by insiders as well.

Another example is Facebook (Meta), Mark Zuckerberg is the insider shareholder which owns only 14% of shares and also has voting rights (Class B shares).

If a company runs into deep trouble & triggered loan covenants, then lenders can essentially run the company via board control. Employees can also control company (union employees or through ESOS). Many listed companies were also once government owned which are then privatised.

When you analyse a company, your first step should always check who are the (largest) shareholders first.

Case I - Disney in 2003

Top 20 Disney shareholders are mutual funds. If they don’t like what Disney is doing, they won’t fight but will just vote with their feet and sell the shares. There are only 2 insider shareholders in this list. Michael Eisner the CEO (actual insider) and Roy Edward Disney, nephew to Walt Disney, who owns <1% of the total shares (passive insider).

Nobody has incentive or power to pushback, leaving the management / CEO to call the shots. Most older public listed companies are like this, no big shareholders to push back on management decisions.

Case II - Vale - voting (ordinary) vs non-voting shares (preference shares) & golden shares

Vale, a Brazilian mining company that was previously government owned until about 30 years ago which was then privatised.

Preferred Shareholders have no voting rights but is 1 pecking order in terms of residual claims above ordinary shares (with voting rights) and are entitled to annual dividends.

Largest shareholder in Vale today is 8.07% ownership by Previ, Brazil’s largest pension fund. The golden shares owned by the Brazilian government has the following powers:

The same political rights as holders of common shares, except for the ability to vote to elect members of the Board of Directors, which will only be guaranteed to holders of the preferred shares of the special class in the cases provided for in paragraph 4 and paragraph 5 of Article 141 of the Brazilian Business Corporation Act;

The right to elect and remove a member of the Fiscal Council and the respective alternate;

Limited veto power over certain Company decisions; and

Priority in receiving dividends.

and have veto powers on the following:

A change in name;

A change in the location of head office;

A change in corporate purpose regarding mining activities;

Any change in the by-laws relating to the rights afforded to the classes of capital stock issued;

Any change in the by-laws relating to the rights afforded the holders of Golden Shares;

Any liquidation of the company;

Any disposal or winding up of activities in any of the following parts of our iron ore mining integrated systems: mineral deposits, ore deposits, mines, railways, ports and maritime terminals.

Source: Vale’s ESG/shareholding structure web page

Here’s a litmut test. As a business, do you want to pay the most taxes or least taxes to the government legally? Say you came out with the most optimised tax plan & propose to the board. How do you think the decision will be made? In making investment decision, do you explore more mines in Brazil, or Canada?

Bottomline: Decisions will be altered depending on who’s pulling the string.

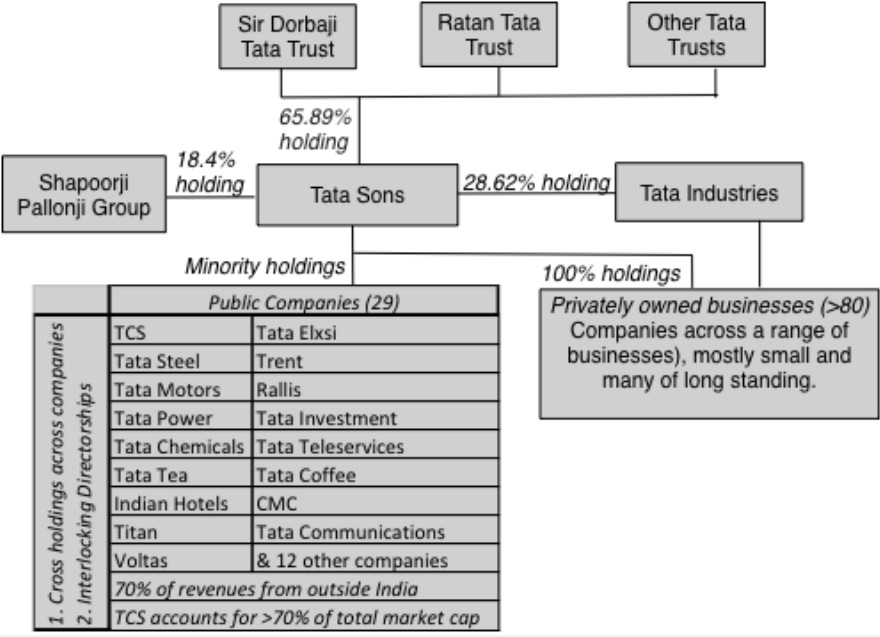

Case III - Tata Motors - Cross & pyramid holdings

(Prof’s slide uses 2013 shareholding list of Tata Motors but I have updated it to the latest)

There are at least 5 entities (back in 2013) in the shareholding of Tata Motors that are related to Tata’s group of companies. This a reflection of most Asian business history before listing of their businesses. During the privately owned days, the way they raise capital is to funnel capital from related entities, i.e. the better/stronger company fund the weaker companies during different business cycles.

Also, any big decisions made by any of the separately listed companies will be influenced by the holding company which poses governance issue. There is also conflict of interests which may either benefit or weaken the business of another related entity.

When you buy any of these related listed company shares, you are essentially buying the entire family’s group indirectly.

Sometimes a holding company will have another holding company, and another holding company. If the ultimate top holding company controls the next second layer of holding companies, it will essentially control the bottom operation company, despite only owning a small percentage directly. Do the math!

Sometimes a benevolent family makes good decisions, and they usually do when they reach until this stage. But it still poses governance issues especially when things turned south.

TCS (Tata Consultancy Services) is currently a US$140 billion market cap company, the sole engine that is driving most of the Tata group growth, in contrast, Tata Motors is only US$17 billion market cap. Other companies in the group are “living off” the success of TCS. If you are a shareholder in TCS, would you be happy?

Family group interests are going to be up first against individual companies in the group.

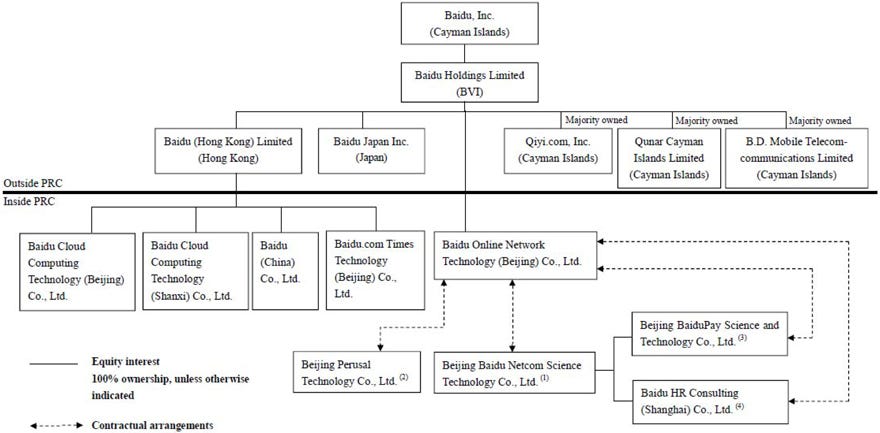

Case IV - Baidu, legal rights & offshore structures

Baidu’s business is entirely in China but the listed US entity is only a shell company based out of Cayman Island, which holds another offshore BVI shell company.

Companies in China and especially those in the sensitive economies like Tech are not allowed to list shares directly outside of China. If they need to raise outside capital, a Variable Interest Entity (VIE) is exactly the kind of structure that is needed. This is like having a cake and eat it too. If 1 day the Chinese government announced that these contractual agreements are null & void, then investors of the listed US entity are essentially holding just shell companies.

This is what happened in the past 3 years of Chinese technology stocks sell-off. Investors are selling off shares in anticipation of any of such bad news. Even when times are good, as a shareholder of the shell company, you as a shareholder still do not have any rights.

In footnote of the structure above. Beijing Perusal Technology & Beijing Baidu Netcom Science are owned by employees of Baidu, as well unrelated third party individuals rather than direct link to Baidu operating company in China.

Case V - Back to Disney, in 2009, the Job factor

Before 2009, you have no hope as a Disney shareholder, you just go along whatever the management says as a shareholder.

Steve Job first invested in Pixar in 1986 for $10 million when he was ousted from Apple and was running his Next company. The valuation he got wasn’t something that George Lucas was happy of and before Jobs came in Pixar had a hard time raising funds. He continued to further invest in Pixar to reach $50 million as the company was burning cash fast as they ventured off to a hardware business. This upsized investment gave Steve Jobs control of Pixar & begins the many collaboration with Disney on animation projects.

Long story short, Pixar actually got listed in the same year as Netscape in 1995. It’s share price performance (at $1.5 billion valuation) was actually better than Netscape due to the success release of Toy Story.

In 2006, Disney bought Pixar for $7.4 billion in an all-stock deal and that’s how Steve Job ended up as the largest shareholder of Disney. Bob Iger mentioned that this was his first & best deal in Disney.

Now, when you have Steve Job as the biggest shareholder, there’s no such thing as going along with the management!

We all know that in this period, the movie business is undergoing transformation. Netflix is already in the process of transitioning from mail-order DVDs to streaming. Disney is the most legacy business ever in the industry and is needed to get a kick from someone like Steve Jobs.

Case VI - The LBO of RJR-Nabisco by KKR

Even as a lender, you must also protect yourself or you are going to get ripped off. Is a matter of when rather than whether, no matter how reputable the company is.

In the 1980s, investors of AA-rated bonds issued by RJR-Nabisco saw their bond value declined by half as it got downgraded to BB ratings after a Leveraged Buyout (LBO) announcement from KKR, a private equity firm.

For some historical context, RJR was a cigarette company that first merged with Nabisco, a biscuit company to dilute the unhealthy image of a cigarette company. 3 years later in 1988, KKR executed the largest buyout at that point in time to takeover RJR-Nabisco for $25 billion. This transaction was eventually documented as a book & a movie due to its corporate raider-ship, greed & betrayal episodes (perfect as a story like The Big Short).

Anyhow, as LBO involves huge debt burden injected into the company, this increases the risk & hence cost of funding for the company. This is why existing debt suffered a decline & ratings downgrade.

Shareholders & lenders are also in conflict when for example shareholders demand higher dividends which may hinder the company’s debt repayment capabilities. Any significant capex even if is in all-cash without new debt will also put lenders in danger.

Lenders only care about getting paid back on their interests & principals, versus a shareholder that wants growth. As a company, once you have debt, all your decisions are skewed as well.

Efficient market hypothesis, between the company & the market

Bad news is always managed to allow the minimal effect on the share price. Hence, that’s why bad news is usually announced at market close of Friday in hope that investors will forget about it on Monday.

But they don’t & that’s why Monday’s share price usually has weak openings.

Another approach is to bundle bad news with good news. i.e. “Revenue up 10% year-to-date (but bottom-line declined by 25% this quarter).“

There are also outright frauds, embezzlement that sometimes lasted for decades.

On the flip side, share price reactions to bad news can also be overshoot, which provide good opportunity for those who knows how to value.

Irrationality exists if they are people who still thinks Elvis Presley is still alive. If they come in crowd, they can move prices. This is an important concept on the 3 corporate finance decision. Sometimes good decisions don’t appear to be good in the short term, & vice versa. Management also tries to hack this by focusing on only making decisions that would affect share price in the short term.

Flipping again, markets maybe thinking far too long term ahead. Think of money losing tech companies with sky high valuation. And why low P/E stocks still remain low while high P/E stocks keep climbing,

Efficient market or not, it is much messier than we thought. If you think regulation is what you need, it makes things worse. The most regulated industry, banks, are the culprits in causing meltdown in markets in 2008, and just recently in SVB as well.

Markets make mistakes, correction happens. Managers should just go & do their thing while markets do theirs.

What are the social costs & benefits?

Not necessarily only bad companies create social costs (tobacco/casino), good companies do produce social costs as well without knowing it (social media). Social costs are also in the eyes of the beholder, without getting any consensus.

If you weigh on social costs/benefits too much, you will face decision paralysis. ESG will be addressed in the next class. // end of Class 3 Corporate Finance.