Class 17 Valuation - Pricing 101

As Oscar Wilde says: "A cynic is a man that knows the price of everything but the value of nothing"

Today we’ll change gear and talk about pricing. When “valuation” is being used outside, they are actually pricing in disguise. Whether it is multiples or comps, people like to price things. Analysts often justify there are less assumptions to use if is pricing vs. intrinsic valuation.

It is true that a lot of assumptions are used for DCF but is it true that there’s no assumption for pricing?

When you are comparing a PE ratio of a company vs. the industry. There’s an assumption there actually, implicitly.

Secondly, the more important consideration is about statistics when comes to using pricing to value. This is an important skill that is needed in understanding pricing. That’s because with so many data points where each are often contradictory, statistics help in understand them.

When all data points are plot on a graph, we don’t often see a “normal distribution” in finance.

For PE ratio, the distribution is often skew positively. The lowest ratio is zero. (If company is loss-making then PE is not taken into account as it is meaningless.) Thus, a right tail distribution.

The average PE is often overstated, which is why the median PE is always used as best practice.

A stock of PE 12x vs industry median of 20x - is this stock cheap?

You should next ask what the growth rate of this company is vs. the industry. Then next is how risky the company is vs. the others. Lastly but not least, what’s the ROE of the company.

After clarifying these questions, you will probably find out that this stock does deserve to stay below the median and hence stays “cheap”.

For every multiple we observe, we must ask some questions then only we can do pricing well. As an intrinsic valuation advocate, Prof. has no issue with people using pricing when it is backed by answering some sensible questions.

Key Drivers for Pricing

As simple as supply & demand, which is compounded by mood & momentum. In fact, behavioral finance becomes an important subject for past decade to understand why people price things beyond its value.

There’s a process to value, and there’s a process to price. Most often there’s a gap between these 2 numbers.

Question is then; will they converge? In efficient market, there’s actually no gap. Price already reflects the value. Buy index funds in this case!

In the value world of Omaha, they would assume that the price is always wrong. Hence a stock can be either undervalued, or overvalued. This is why we take this class.

Next, the pricing extremist where they don’t believe intrinsic valuation will opine that value will never converge with price. They think value is something intellectual, pricing extremist is a pure price trader to just “buy low & sell high” or “buy high & sell higher” as long as they make money.

As a valuer, we face a dilemma of how big this price and value gap is, and then when or how this gap will converge. A few ways to address the magnitude is to:

Have a margin of safety, ensuring the price is way below value

Strengthen the valuation by collecting more info

Have different valuations based on scenarios

Deal with the uncertainty in the valuation itself

To address the gap convergence, you will need to:

Lengthen your time horizon

Look out for catalyst that would cause the value to materialise

Active investors will create that catalyst themselves, or we would anticipate a management change (like how Starbucks announced a new CEO and price surged 24.5%, erasing 2024 price losses and is also the single largest 1-day pop since IPO in 1992). Another prominent event-based catalyst would be M&A, where the acquirer agrees that the target is indeed undervalued and launch a tender offer.

Apple is a classic example that prof traded in and out of it based on his valuation.

The % difference in negative above (in right column) shows that the valuation that prof did for that year surpasses the price, indicating an undervalue of Apple’s share price.

(He’s a big Apple fan & hence has upside biases on it and thus have valuations that surpass prices. Another observation is that his valuation is not linear up but also has down trend in year 2013 & 2016.)

A closing thought from Wizard of Oz. They never found Oz, but their journey is what they are searching and found after all.

This is the same in Valuation, there’s no 1 final answer or destination. Not only in that but also no fixed number on the assumptions to use, in deriving the final answer. You keep learning by facing obstacles (just like Dorothy on her journey) and getting unstuck from it. You learn to reason your assumptions to an answer. i.e. Don’t be cursed by Google Search but learn on reasoning from that search query.

Relative Valuation as Pricing

Pricing is essentially what others are paying in setting that benchmark price. To break it down, to do pricing, you’ll need the following:

Another comparable asset with prices

Standardise this difference in prices. A big house will have a higher price compared to a small house with lower price even if they are neighbors. So, you standardise them into a common metric by dividing into something common. In housing will be “$ per square foot”, in finance, it will be multiples of earnings.

Since is so simple, this method in relative valuation is thus so much popular than intrinsic valuation. Prof proofs this through his research that:

Almost 85% of equity research reports are based on multiples and comps

More than 50% of M&A transactions are based on multiples

Where there is DCF, they are pricing in disguise. Is usually being done to justify a multiple, and even so the terminal value used in DCF is based on a multiple.

What’s so attractive of Relative Valuation? Is easier to sell:

a 100x P/E is cheaper than a 200x P/E

a 12x EV/EBITDA is easier to justify when a comparable is also 12x, versus justifying a 12% forward EBITDA margin assumption

Follows the trend and don’t get fired even if wrong. Compared to going against trend, be a contrarian, got it wrong, and then get fired.

Prof used to be against pricing since he teaches intrinsic valuation but he gave up on this thinking knowing that his students will eventually end up doing pricing anyway. So he introduced pricing in his syllabus to make sure his students do pricing correctly.

Price vs Price Multiple

The 1st step is to standardise pricing as mentioned earlier using the house example. Otherwise a Berkshire Hathaway Class A stock at ~$690k will always be more expensive than a sub $1 penny stock.

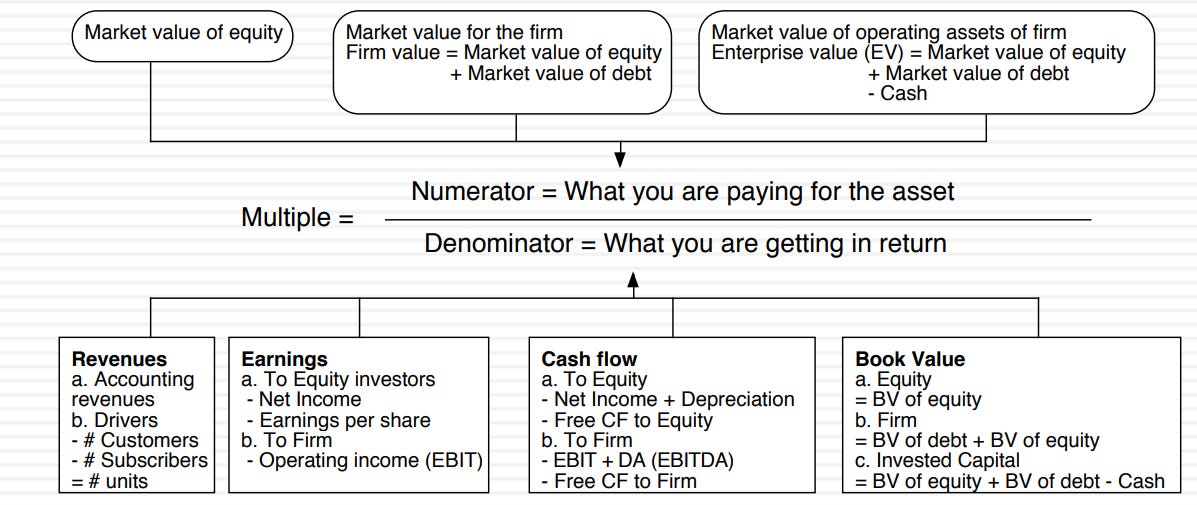

Cheap or expensive is measured by multiples of “something”. This is “something” is what you will be getting in return. It can be Revenue, Earnings, Cashflow or Net Assets/Book Value.

The easy thing about pricing is that it can quickly use to measure loss-making and even pre-revenue companies, e.g. Price/Revenue, Price/User, Price/Impression if you are desperate.

There are 4 steps:

Define the multiple - your (forward) P/E may not be the same as my (trailing) P/E

Describe the multiple - use the data to find all the multiples with other companies to judge what is the range

Analyse the multiple - understand the drivers behind the multiple. If is EV/EBITDA - understand how the EV and EBITDA is built up. Then also understand the relationship of the multiple with these drivers.

Apply the multiple - as the last step by knowing which universe of stocks you want your comparable to come from

Step 1 - Defining the multiple

First, the numerator and the denominator should be from the same concept of either equity or firm value. If is P/E, that’s because it is “equity value over earnings belonged to the equity holders” If is EV/EBITDA, that’s because it is “Enterprise Value over Earnings that the firm has before paying off debt.”

What about P/Sales? This is where the desperation comes in.

Another layer to P/E is sometimes Earnings are defined in many ways, either in Last Year, Trailing 12 Months, Forward Earnings Next Year or even Next 2 Years.

Or even before/after extraordinary items, before/after stock-based compensation, fully diluted, partially diluted, and 40+ more definitions depending who is using it, to sell or to buy, bullish or bearish on the stock.

To be truly consistent on tech stocks where there are a lot of stock options, the discipline should be to use “market cap + equity value of the option” dividing by the earnings over fully diluted shares. Otherwise the P/Es are always low for tech stocks which is the current observation.

Next is EV/EBITDA.

Why do we substract Cash out from Enterprise Value? Then why do we use Book Value of Debt instead of Market Value, since we’re using Market Value of Equity?

Since we’re not including income from cash by using EBITDA, then for consistency is to also exclude cash in the numerator. Cross-holdings and associate company’s profits are also including in EBITDA. Hence, adding back Minority Interests in the numerator is also makes sense.

Step 2 - Descriptive Test

The objective here is to use statistics to stress test the reliability of the multiple. Some questions to ask are:

What is the average, median & standard deviation of this multiple?

How large is the outlier?

What is the trend like over the years?

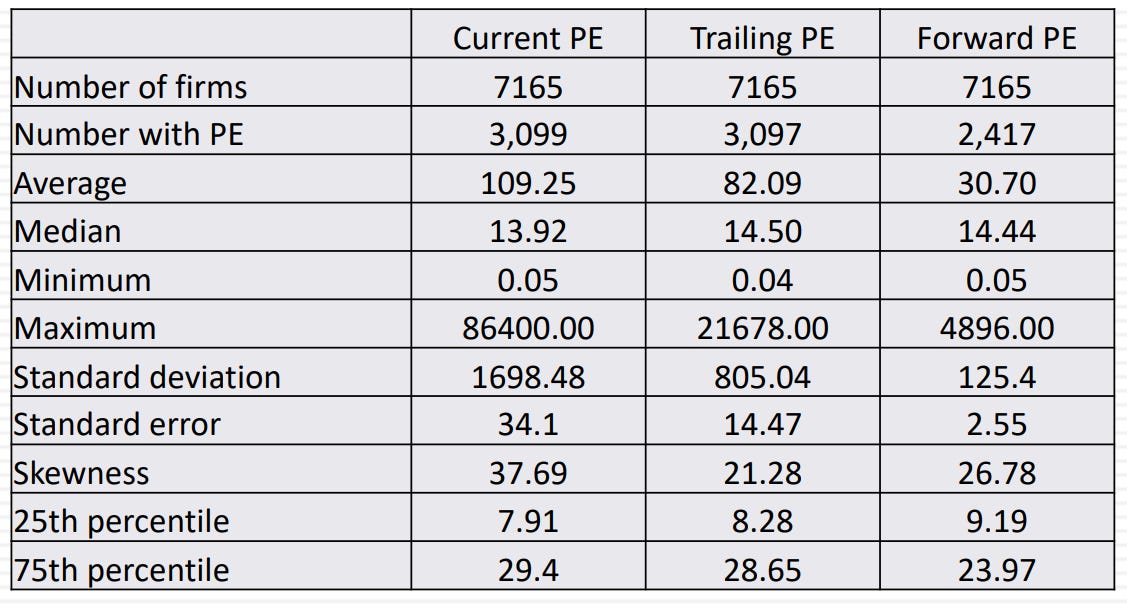

Prof do an exercise every year on 1st Jan using database like Bloomberg or Capital IQ to download all the multiples data since the 90s. Table below is a summary from his extract in January 2023.

1 obvious observation is that by using PE as a multiple, more than half of the firms are excluded since they are making losses. The disappearance is greater when comes to Forward PE too as there are no analysts coverage on them. Then, the big difference between Average & Median due to outliers. Note the Min & Max numbers as the outlier too.

The beauty of a standardise data is now that we can compare globally:

Key is to observe the outliers of Canada’s 10.25x, Eastern Europe’s 10.58x & LATAM of 10.5x. They look cheap because there’s a reason which need further investigation. For example, commodity exposure, political stability risk, etc.

Japanese P/Bk are unusually low is not due to them being cheap (pre-Buffet’s run up) but due to their accounting rule that allows provisions to be built up on their asset book, inflating the book value.

Due to the above reasons, is also very dangerous to have a rule of thumb to say that 6x P/E is cheap. This is especially true for private markets practitioner in their “investing discipline” of buying cheap only.

On next class we’ll further deconstruct pricing….

// end of Class 17 Valuation