Class 15 Valuation: More excursions on the dark side of valuation

Rather than "emerging markets", could it be "submerging markets"?

Last session we learned to value young companies, today we’ll dig deeper into the dark side of valuation and focus more on valuing emerging market companies.

Bad corporate governance is not just applicable to emerging market companies, but it can be seen all over the world. Facebook & Google are examples of having bad corporate governance actually, as prof said.

Say you finish valuing a company with bad corporate governance at an intrinsic value of $100 million. Do you discount it further for bad corporate governance?

No but why not?

That’s because the effect of bad corporate governance is already reflected in the cash flow. Margins, ROIC & terminal value will be low as you would have correctly estimated (due to inefficiencies caused from bad governance), vs. an industry average.

The cynics will always ask, “but where is the corporate governance that is already reflected in cash flow”?

Prof will give out a mechanism to estimate this discount in this class.

Next, is the distress factor.

Say you calculated an intrinsic value of US$1 billion for a distress company after making realistic assumptions with a high cost of capital, lower to negative margins or growth, etc. Will this value be too low, reasonable or too high?

Is most likely too high because DCF is meant to value a company that is at a going-concern.

Why not look at increasing discount rate? You can try doing 1,000% cost of capital but fundamentally discount rate is to capture operating risk that still is in going concern. A high discount rate just means high operating risk which would still generate some level of operating cash flow in the future, despite the cash flow being tepid.

Prof. will share how to estimate the equity (option) value for such distress situation.

// Being Class 15 Valuation

Recap from previous Amazon’s valuation exercise where the intrinsic value was at $35 but market value was at $84/share. Significantly overvalue, unsurprising during the dotcom boom.

However as seen in the chart below, market value corrected post dotcom crash, even below the intrinsic value that has been adjusted for the crash at $20/share, with a high failure rate.

This was a signal to buy, in hindsight for us, and was the first time prof bought it back in 2001. He does a “maintenance valuation” on his stocks annually to check if share price has gone past his intrinsic value, for a signal to sell & take profit. Prof has tripled his cost on Amazon holding. For the past 20 years, he has traded 3 times and is currently holding his remaining position in Amazon (as of Spring 2023).

Market is most often “more wrong”.

Never say “never buy this stock (due to hype)” because the price will be attractive enough for you to buy it eventually, i.e. at the right price. This is why we create a watchlist!

Prof has updated his Amazon valuation every year from 1997 until recently in 2023. This is dedication but not unexpected if you treat it as your retirement fund.

Another note is that there are tons of books out there on how/when to invest, but very little to none on how/when to sell. This gap doesn’t match with the idea of value investing where you sell when the price of the company becomes overvalued. Too much knowledge shared on buying but not enough on selling.

Self-evaluation

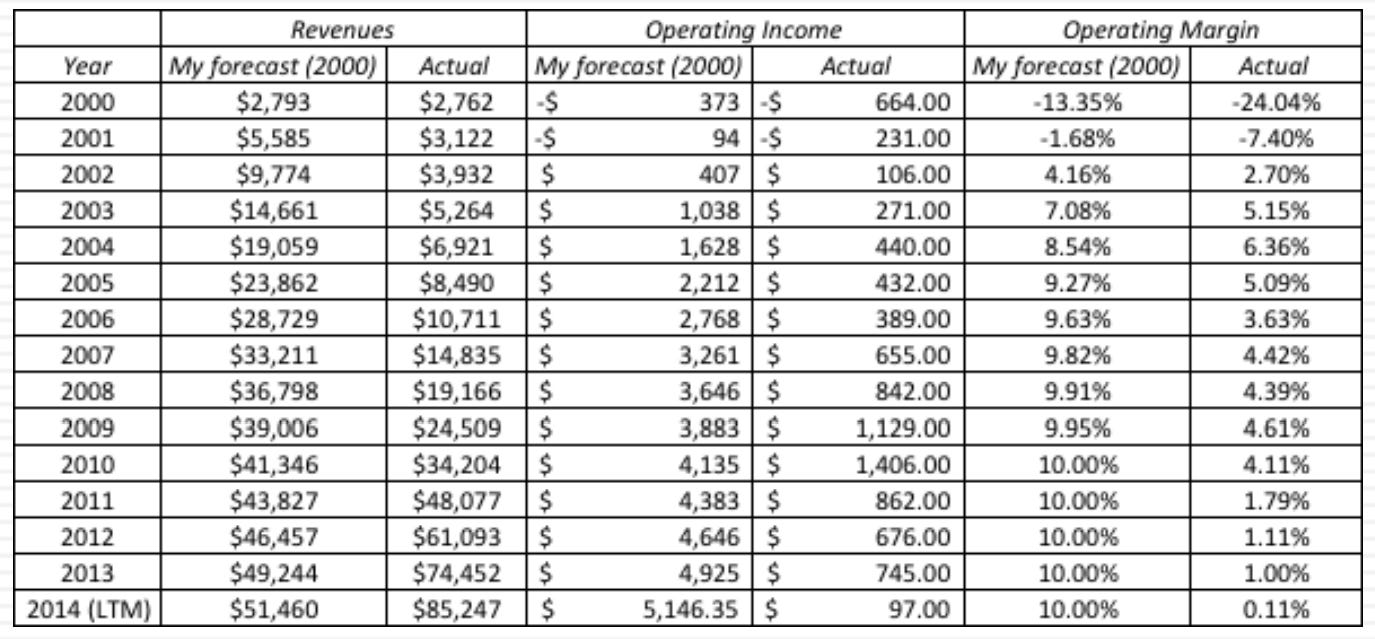

Prof evaluated his valuation on Amazon as shown in the following table with the actual numbers as years passed. Is quite depressingly inaccurate especially it comes from him!

Some under-estimated & some over-estimated. In 2014, you can see that prof’s projected revenue by 2014 will be at $51B given Amazon’s positioning in the retail market, but it actually did $85B with additional revenue streams (e.g. AWS).

While prof’s forecast for operating income is way over-estimated with a $5B number while Amazon only did $97m.

Between 2010 to 2014 where the operating income declines, we all know that it no longer just a retailer company but a disruption platform where it can replicate their online retail to online “anything”.

When you are a disruption platform, the upside has widen a lot with no limit on TAM. Upside is you can be a $2T revenue company with many verticals but the downside will be distraction. Somewhere along the way you will be less efficient.

During the 2022 tech winter, prof updated his FANGAM stocks valuation in this blog post. Full valuation spreadsheet of Amazon and a ~1 hour explanatory video as study reference.

To re-iterate, every big old economy business can be disrupted by Amazon. A survey of CEOs was held on world largest companies by market cap on which company that they feared most. Walmart, Fedex, UPS & even JP Morgan’s CEO all mentioned Amazon.

Amazon is like Thanos, in whatever business that it touches, that industry will start to see their margin drops. The day that Amazon bought Wholefoods, the collective market cap of groceries companies drop by $50B in US. Here’s a followup on how Wholefoods has changes 5 years after.

In contrast, what does Netflix looks like? A hamster in a wheel. It throws in a 100 new shows everyday, 95 are unwatchable. You’ll have more false start in Netflix than any other streaming services. Based on this narrative alone, there’s no need to begin valuation.

Valuing young company is hard, 1 comfort is to know that even the insiders will have a hard time valuing themselves.

1. Mature companies

What makes mature companies easy to value? There’s a lot of history to study, including all the bad habits/legacies that slowly leads into its decline.

Until an active investor comes in to wake the management up. There are 2 pathways, the status quo, or to make a change.

This is valuation becomes harder. Like the multiverse, 1 pathway alone will leads to many different characters & assumptions. Expanding on this by asking a few questions:

What are the cashflows from existing assets? With status quo, only 1 number (valuation). By choosing an alternative to say expand, there will be different numbers.

Who will run the company. Again, status quo, same number with steady dividends or free cash flow but if is someone else, a new CEO, then there will be options. A new CEO will opt to reinvest existing free cash flow to find growth opportunities.

How risky are you? At status quo, 1 number for a conglomerate with 8 businesses. Or maybe you break them up to give different numbers.

Nothing stops you from valuing the company more than once actually.

An example, Hormel Foods, 1 of the oldest food company that you never heard of, but with a product that you must have known. SPAM!

It was a traditionally run company with no debt & low re-investment rate.

First we value this status quo as prof has done:

It has low expected growth rate of only 2.75%, low reinvestment rate of 19.14% & with a low debt ratio of 10.4%. The value for this is ~$32.

Then prof simulated a normal growth scenario with expected growth rate of 5.6% & bump up the reinvestment rate to 40%, as well as increase debt ratio to 20%, as illustrated below:

Value for this growth scenario is ~$38. Breakdown below.

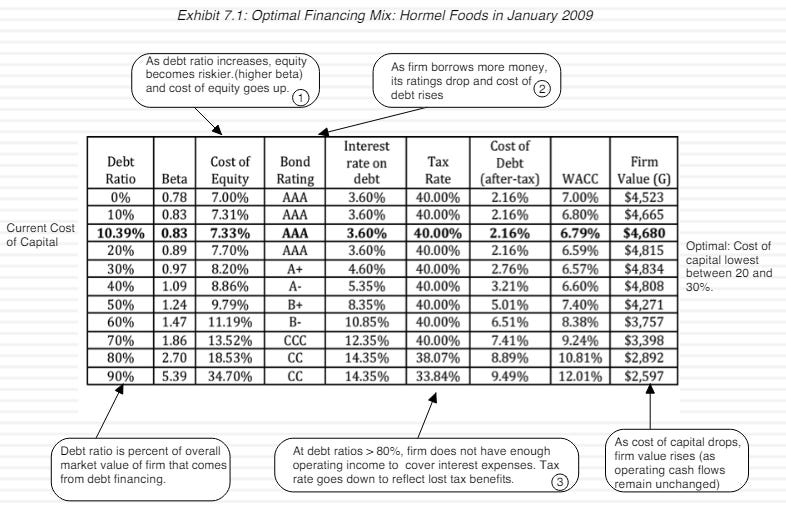

Why increase debt ratio to 20%? This is to reduce the cost of capital from 6.79% to 6.63%. A quick primer on optimum capital structure as taught by prof in his corp finance class:

[placeholder for future notes link on this CF class]

Prof could use the most optimum debt ratio of 40% as shown with the table above but he wanted to be conservative and used 20% instead. Very mechanical calculations with the following principles:

As debt ratio increases, cost of equity increases in a single direction due to beta increases. (Residual income to equity holders become lesser as debt increases due to increase in debt repayment. A highly indebted company is then way riskier than a zero debt company in the same business.)

As debt ratio increases, the lender also demand higher interest rate as the ability to pay from operating income (Interest Coverage Ratio) becomes lesser.

Cost of debt (after tax) is definitely cheaper than cost of equity leading to cost of capital (WACC) that is lower than just Cost of Equity alone.

The trade off on the above is that there’s an optimal point (at 40% debt ratio for Hormal). Beyond that, insolvency risk kicks in due to inability to repay back.

So why 20% debt ratio as chosen by Prof?

Perhaps this can be a good practice. If there’s a likelihood of a mistake like in any or most matters. Is better to undershoot, than overshoot.

So, end result will either be status quo or growth.

To effect change on management, there must be a Carl Icahn as an active shareholder.

Based on the actual shareholding of Hormel, it is still substantially controlled by the family hence change will be of a low probability.

Using the expected value concept of status quo being 90% chance and growth of 10%. The expected value is now 90%($32) + 10%($38) = ~$32.50.

This expected value concept is an important concept in this class session, as a way to account for risks, rather adjusting discount rates.

Next week will be a valuation on EasyJet, a low-cost airline from UK. The point in time of valuation will be during the Brexit voting months. Prof. uses 3 scenarios of hard Brexit, soft Brexit and no Brexit & came out with the same expected value of valuation.

2. Dealing with distress or declining companies

Is often more psychological when comes to such companies. From historical, you see declining revenue, eroding margins & ROIC ,to the point of having multiple years of losses.

Is not about growth but shrinkage through shedding assets, cutting costs and retiring debt.

When will the good times come? There won’t (for a structural decline in the industry or a company that losses technology edge). A constant growth rate is thus impossible. Terminal value hence becomes literal, or in another words, liquidation value.

As an investor, the worst case is that managers of these firms are in denial & continues to make investments that don’t return in growth. Revenue will still grow in a slower pace but it will destroy value in the long run. These situations are not strange as you would see a declining company hires a (outsider fresh blood ex big tech executive) CEO in hopes of turning things around.

Thus when valuing a declining company, key is to also assess who is the CEO, you don’t want a visionary; hence an ex-big tech executive won’t be suitable.

A classic example is JC Penney actually hired an executive from Apple to turnaround their business. Just like how Marissa Mayer of Yahoo was an ex-Googler.

JC Penney’s turnaround story was a disaster. A timeline to study.

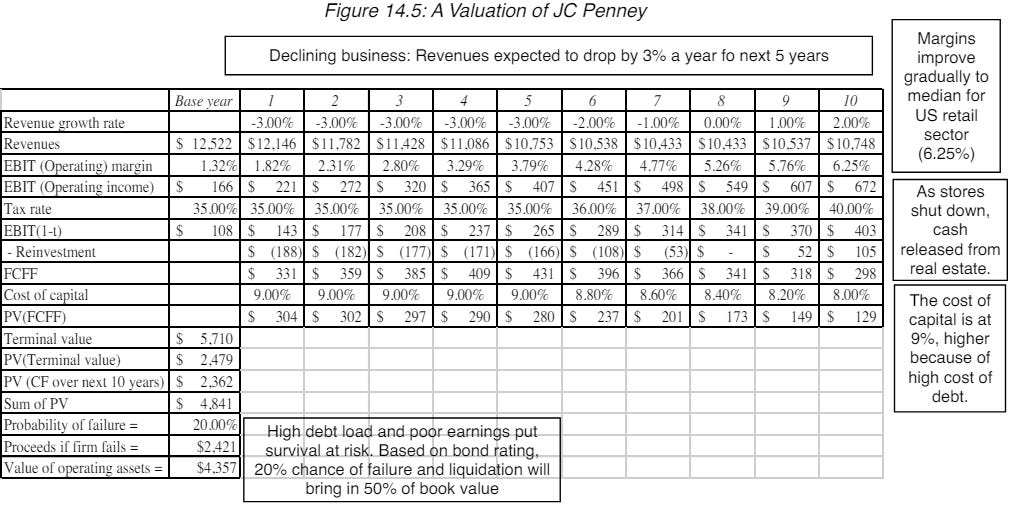

Below is how Prof valued JC Penney.

Key drivers are -3% revenue growth, -ve reinvestment, meaning company is getting cash back by closing down stores. Add in a 20% failure probability with half of what he valued.

DCF overstates a distress company’s valuation, how do we deal with it?

It can be formularised as:

Value of equity = DCF value of equity * (1 - distress probability) + Distress sale value of equity * (distress probability).

Probability can be obtained from bond ratings agency as each rating will have such default probability.

Prof uses Las Vegas Sands (LVS) during Great Financial Crisis as another example. Prior to GFC, LVS had borrowed a lot of money for their casinos expansion globally. It was a high growth / high beta stocks.

When GFC hits in 2008, the chips came tumbing down. There are rumours of LVS can’t service the debt & will go bankrupt. Evidently share price fell by ~90% from 2007 peak to the trough of 2009! You can see a little small sharp dip too when the world closes during March 2020 of coronavirus pandemic below.

So prof value it with the following drivers to assess the chance of survival, or rather how distress can it be. First step is to value it as a going concern.

There’s actually potential to double as the distress price back then was at $4.25 while prof valued it to be $8.12. Did he bought it? Not quite as we’re only done the first part.

Now is to value the distress value using the bond probability of default. LVS was rated as B+ hence the likelihood of default is 28.25%.

But Prof wanted to be more accurate (as the bond rating may get downgraded later anyway), so he uses the bond market price instead in estimating the default risk. As a bond with its traded price would reflect reality better.

LVS had a B+ bond with 6.375% coupon, maturing in 7 years and was trading at $529.

Through an excel spreadsheet, the above inputs are used to produce an annual default probability of 13.54%. To ensure survival of at least 10 years, this annual distress rate is then compounded for 10 years to have 23.34% as the surviving rate. Thus, 1-23.34%=76.66% becomes the default probability.

Using this bond price approach:

Intrinsic value of $8.12 * (1-76%) + Distress value of $0 * 76%) = Expected Value of $1.92. Far lower than the traded equity price of $4.25!

P.S. a small commentary by Prof on this exact same time where he visited the Bellagio.

3. Emerging Market Companies

The initial reaction is usually accounting (that diverges from what the West is used to). This is not true now a days as the world of accounting is more converging than diverging compared to earlier years.

Yes, there is risk but it should be assess with the specific nuances rather than taking an easy approach of increasing the discount rate for example.

A company like Coca-Cola, from the developed market is more exposed to the emerging markets actually. Should we discount it heavily then?

Same with currency, as that it shouldn’t matter. You can actually value any company in any currency by also using the same country’s discount rate & cash flow. Thus if you are using a high inflation currency (a weaker currency), the (nominal) growth rate and discount rates should also be higher.

From an investor point of view that is globally diversified, currency risk don’t matter (but maybe a bit!) as companies that are affected by currency devaluation is balanced off with companies that are enjoying an appreciating currency.

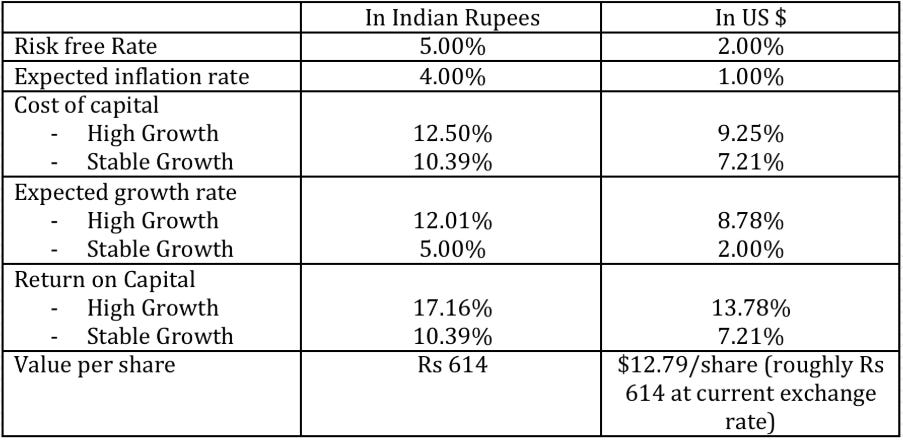

Prof uses Infosys, an Indian outsourcing company as an example:

Both methods of using different currencies in Indian Rupees & US$ don’t matter as the end value per share is the same.

How about bad Corporate Governance (CG)? That the truth is it happens at both side of the world. There is a perceived bigger CG issue in emerging markets mostly due to the history of how such companies are built, as that many are family run with tight control, causing big conflict of interest.

Again, should you have a discount rate for bad CG?

Let’s use another Indian company - Tube Investments, a family run bicycle manufacturing company that prof knows his whole life.

The company was traded at 102 Rupees in 2000, with super high re-investment rate of 112% but with a Return of Capital of 9.2% where the Rfr was already 12%! The company was actually losing money with their investment versus just buying a government bond. The more they invest for growth, the more money they are losing, destroying value rather than add.

Since the company wants to grow. Prof lowers down the reinvestment rate by half with an EBIT growth rate of 5%.

The result is an intrinsic value of 62 Rupees.

What the family responded to prof? We shall re-invest more!

First rule when you’re in a hole, is to stop digging! A lot of times doing nothing is better than doing something, rather than fixated on growth, growth, growth.

Few things can be done on doing nothing:

Reduce reinvestment rate

Or find projects that (can really) increase ROIC

Both of the above will increase value mathematically & in reality too if it really does executed well on doing nothing.

On cross-holding, this is a result of historical design of family owned groups rather than being deserved of a penalty. The older a company gets, the more crossholding there is as evident by prof’s chart below on Tata group of companies:

The blue color bars are DCF of each business from their actual operating assets while those in read are values due to cross holdings. TCS or Tata Consulting Services has the least cross-holding value is primarily due to the fact that this business is the newest of the lot. You can assume TCS’s shareholding has Tata Chemicals, Tata Steel & Tata Motors!

Many years back, Tata family wants to build a steel business & where do they source the capital from? From an existing cash flow business & for example Tata Chemicals or Tata Motor. Hence the beginning of 1 company owning another company & vice versa, an internal capital formation to generate funds for future businesses.

No conspiracy though it does complicate valuation.

On Truncation risk, where the risk of value is shorten or truncated to the point of even to zero. Events like natural disaster, terrorism & even nationalisation are all possible situations where businesses will become zero overnight. Prof highlighted that the way to treat such risks is the same as any other. That is is to assign a probability & value of it if such event happens (i.e. the expected value).

As an example of a valuation with truncation risk, prof uses Aramco, a Saudi’s national oil company with a US$ trillion market cap that is outside of US & non-tech.

This is also 1 of the few times you use a finite life of 50 years to value a company coz of oil reserves that depletes without any replenishment.

A fair value of $1.6 trillion is obtained but it’s not being adjusted yet for truncation risk.

Buying Aramco is basically buying the country (80% of Saudi’s GDP is from oil) in the center of geopolitic risk & not even that but also buying the ruling family. This is a clear case where country risk is apparent and is not reflected in any numbers including the country’s rating.

So regime change is possible with prof assigning a 20% probability.

Hence the Expected Value becomes = (1-20%) * $1.6 trillion + 20% * $0.8 trillion given the regime change may effect higher taxes on the company. The final valuation is then $1.48 trillion

In summary, 2 different narrations, 2 different calculation & not to mix them up in the valuation.

4. Valuing Finance Service Companies

Pre-GFC of 2008, people value banks using DDM (Dividend Discount Model); the last bastion for DDM. 2008 changed the game as trusting the people to run the bank effectively to produce dividends is broken.

Secondly, the notion that banks couldn’t be riskier as regulators prevent them for doing so is also a big assumption that is broken. This is the Faustian Bargain (deal with the devil) being broke.

Let’s revisit pre-2008 on how you value a bank:

Operating cash flow from operating assets are basically the norm but it will be impossible for a bank due to their opaqueness.

But we are ok with it because somebody is watching them!

This is the reason for DDM, where the only tangible cash flow of dividends eliminates the opaqueness of bank’s cash flow.

DDM is also easy, as you don’t need to forecast capex & depreciation but just the earnings & varying the payout ratio in forecasting the dividends.

In this last example, let’s demonstrate DDM of a bank, in an emerging market! Double whammy in terms of opaqueness & taking emerging market risk. It is also valued in the local currency of Egyption Pounds.

Few observations:

ROE of 42.48% which is very high but it’s also due to high inflation & high risk-free rate.

Cost of equity is 23.25%! Very high but not really due to reasons above.

Using inflation differential to estimate the Rfr of Egypt. You can see the inflation for US is 1.5% while Egypt is 9.7%.

EPS growth declines in later years with a convergence to terminal growth of 10%, payout thus increases to maintain or increase the dividends.

Terminal growth of 10% is justifiable due to high inflationary environment.

In the next class, we’ll learn how to value a bank post-GFC. Hint: is in the books.

// end of Class 15 Valuation