Class 12 Valuation: Last loose ends & first steps on Storytelling

Keep it simple, in running business, in doing valuation & in storytelling.

The class was held in the midst of the 2023 US Banking Crisis. Prof commented that banks are hard to value because the fundamental of it is based on trust. If everyone decides to withdraw their money from the biggest bank tomorrow, that bank will collapse, doesn’t matter the brand or the size.

This is the reverse of Bitcoin, where it is based on a decentralise system of not trusting & hence created a lot of inefficiencies as seen in high transacting fees. We use trust to create convenience & efficiencies. We put money in the bank & don’t think about it most of the time. This is the benefit of trust; we can carry on with our lives without worrying about our money disappearing.

Especially after the 2008 global financial crisis, trust in the banking system is getting lesser, slowly and surely. With crypto rising, this is a dangerous world we’re living in, to quote.

FYI, YTD ‘till November, Bitcoin itself is up 132%, you can view it more in the post below on how it fared against other asset classes.

As a preamble to the class, let’s examine 2 types of companies with the same financials, same growth & same risk vs ROIC.

Company A is in a single business & has transparent financials.

Company B is a complex firm, in multiple businesses, with opaque structure.

Which firm would you value more highly? But why since the numbers are all the same?

How about, would it be A because it is simpler, or B because it is more diversified?

A dangerous habit in valuation is that we tend to ignore what we don’t know. In fact, what you don’t know is actually more dangerous when comes to valuation.

Valuation aside and from an investor pov, Company A is always preferred.

Next, let’s say we did a DCF & a company is worth $100m, the firm has $100m of debt outstanding but with a price of the debt at $80m.

What is the equity value of the company? $20m or 0? It depends.

We first need to understand why the market value of the debt is lower than the book value. With an increase in interest rate, this causes debt value to drop, make sense in recent 2 years.

Or it could be a distress company & there’s a haircut on the debt.

In the former case, the higher interest rate is reflected in cost of capital, essentially lowering the DCF value. Hence, it makes sense to stay consistent, and deduct the market value of the debt.

If is a distress situation, the market value of the debt could bounce back to book value if fortune turns. Hence, book value of the debt is correct.

Next, let’s examine granting of options to management. This practice is getting more common in-lieu of cash & bonus; however, from an investor point of view, it would be preferred to reward in higher salaries & bonus.

If a CEO has 10m of options with exercise price = current stock price, what effect will this have on investor’s value/share? We’ll find out in the class later.

// Class begins

To continue of if we should add/subtract things out of the DCF value.

Loose end 3: Other Assets that have not been counted yet

A classic case is a business with own properties, i.e. hotels. Say you have valued the business of a hotel to worth US$200m, and the piece of the real estate is US$100m. Does it mean the value of your business is then US$300m?

No.

If you sell the real estate, your hotel business can’t run. The business value already has the real estate value embedded even if sometimes the real estate value is higher. If this is the case, it’s an arbitrage. Buy the company & then sell the real estate.

Same goes for a shipping company. You can’t add back the value of the ships on top of the business value!

In the 90s due to the dotcom boom and overall bull of the economy, a lot of companies have over-funded pension plans. Meaning what the companies promise to their employees as pensions has more than what is promised. In theory, it should be added back since this excess belongs back to the shareholders. However, in practice, prof suggests leaving it since it is cycle dependant, what overfunded can be underfunded as well.

So, what can we really add back to push the envelope?

Unutilised assets like land that are left vacant, or a mansion that is belong to the company but lived by the owner. Both of these examples have nothing to do with the business (not generating cashflow) but are just so happened registered under the company. Case in point, the Playboy mansion that is lived by Hugh Hefner but belongs to Playboy the company.

Loose end 4: A discount for complexity

Or in other words, should we discount companies with complexity?

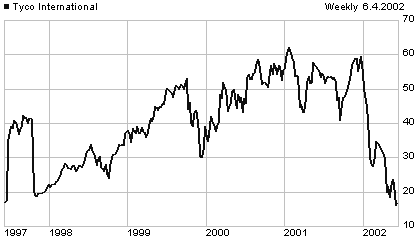

Between 1991 and 2001, Tyco International acquired some 3000+ companies in this period of 10 years led by then CEO Dennis Kozlowski. These acquisitions led to an accounting scandal which overstated its financial results by at least $1 billion to an estimated $5 billion. Lawsuits ensues, including the auditor being sued by investors for failing to detect such frauds. ~80% / US$85 billion of the company’s market cap vapourised due to this.

Prof suggested that we’ll need to measure complexity in order to value complexity.

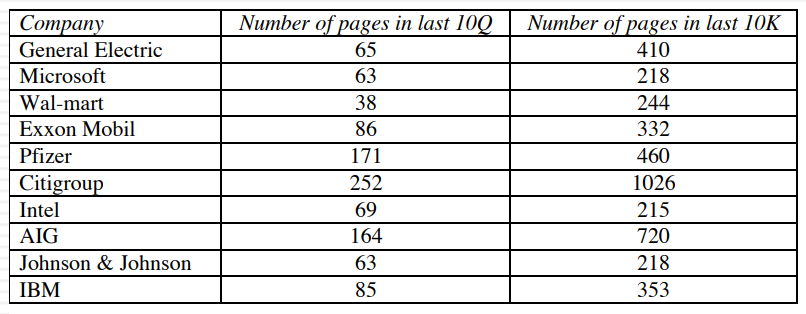

2 methods, 1 easy, 1 hard. Easy first, just by counting the # of pages of their 10K or annual report. For e.g.:

There’s 1 company above (Citigroup) you want to stay away from if you want to do a simple valuation.

Companies in or with businesses in emerging markets, & companies with a financing arm is always more complex to value.

A harder way is to actually break each complexity down & give them a scoring. The higher the score, the more complex it is.

As you can see, crossholdings with minority interests have the highest weighing factor of 20, demonstrating the complexity of crossholding!

There are 4 ways to treat complexities in companies:

Adjust the cashflows, arbitrary

Adjust the discount rate, by 1% higher in Ke (as empirically tested by prof using components in S&P500)

Adjust the growth rate or length of growth period by bringing excess return down to zero quicker (from ROIC>WACC to ROIC=WACC faster)

Value the firm first, then discount it for complexity

Prof actually ran a regression on the 100 largest market cap firms using 4 variables of ROE, Beta, Exp. growth rate & # of pages in 10k to estimate P/BV

The result is surprising with the following regression formula:

P/BV = 0.65 + 15.31ROE - 0.55Beta + 3.04Expected g - 0.003# of pages in 10k.

For every 100 pages of 10K goes up, the P/Bk ratio drops by 0.3%! Simplify is the key.

Citigroup is complex by design when Citibank merged with Travelers to form a financial supermarket. 1 bank is hard enough to value, imagine valuing 2 banks together.

It is often argued that by splitting up mega banks into individual business would create more value than by combining them with too many unknowns or opaque information.

Loose end 5 - Be definitive about debt

You don’t want to unnecessary recognise debt when it isn’t. This causes higher debt/equity ratio which would understate cost of capital.

In general, debt has the following characteristics:

a commitment to make fixed payments in the future

fixed payments are tax-deductible

failure to make those payments can lead to a default or loss of control of the firm to the debtor.

There should also be interest components and debt should then include all leases.

What debt is NOT:

payables or suppliers’ credits

However, when deriving equity value, we should take note of contingent liabilities like lawsuits. We’ll need to deduct the expected value of this contingent liability out by assigning a probability to the outcome.

Loose end 6 - Equity to employees & its effect on valuation

Prof has observed that many of his grads have move to tech employment versus the traditional Wall Street jobs, a contrast to the early years.

A big difference between high finance & high tech is cash! Tech companies generally don’t have the cash to pay Wall-Street like compensations. Hence, the birth of stock-based compensation to incentivise post-grads students to join them, a remuneration scheme that would potentially pay much higher than bankers.

1 of the largest issue with stock-based compensation is to expense them or not to. The accounting standard finally caught up. Prior to this, 1 would argue that because it is non-cash, it shouldn’t be expense.

They are 2 key issues to deal with today:

How to adjust for options or restricted stocks granted in the past

How to adjust for options or restricted stocks that will be granted in the future

From 2007/8 onwards (during height of bull market before GFC?), companies started to give out restricted stocks as part of compensation. Restricted in the sense that you cannot sell or trade those shares for X numbers of years. You have to vest them, meaning to work in the company for X years then only you are eligible to those shares.

This form of compensation is simple.

For past restricted stock grants, you just need to add those shares into the current outstanding shares, effectively diluting the value per share.

To account for future stock grants, you can estimate by using past grants as % of revenue to forecast the expense as part of compensation expense. This will reduce future net profits and cash flows.

Options are harder.

This is because the company is effectively giving you a discount to buy their new issued shares when the options are in-the-money. What companies do is they usually will also buyback those shares.

Excess cash that are supposedly belonged to investors are now used to buyback newly issued shares. This actually lowers equity value.

Let’s illustrate:

Company XYZ has $100m in free cashflows, growing at 3% p.a. to perpetuity with cost of capital of 8%. It has 100m shares o/s & $1b in debt. The value of the company can be calculated as follows:

Enterprise Value = 100/(8%-3%) = 2,000

Equity Value = 2,000 - 1,000 = 1,000

Equity value / share = 1,000/100 = $10/share

XYZ decides to give 10m options at-the-money (with a strike price of $10) to the CEO. How will it affect the equity/share?

None.

Decrease by 10%, since the number of shares could increase by 10m.

Decrease by <10%. Options will bring cash back to the firm but they have time value.

The dilution share count approach

You would adjust the share count by the additional 10m. Hence your equity value / share becomes 1,000 / (100+10) = $9.09/share.

This is only half correct as it ignores the cash that the company will have when the options are exercised. Consequentially, this approach underestimated the equity value / share.

The treasury stock approach

This approach add the cash into the valuation first, before dividing by the diluted shares.

So equity value of $1,000 now becomes $1,100. (10m shares x $10 strike price).

If you divide this $1,100 by the enlarges shares of 110. The equity value / share becomes unchanged at $10/share!

However, it is still not fully correct as this approach do not account for the time value of the option. How about if is an out-of-money option? Totally ignoring them?

The valuing the option approach

This is the correct method. We’ll need to value the option separately. Either by using its existing market price, or through a Black-Scholes model. This derived option value is thus deducted from the earlier estimated non-diluted equity value. Then divide by the current o/s shares.

However, there’s some disclaimers:

Employee options are much longer term than shorter tenure options. This makes certain assumptions in the Black-Scholes model shaky.

Employee options are normally exercised earlier than their expiration, making the European model of Black-Scholes also shakier.

That itself is dilutive but this separated method of equity value minus option value not accounting for it.

That there’s a vesting or lock-in period where the options can’t be exercised.

Using an online Black-Scholes calculator, the following input/output can be use to derive the option value of $5.42.

A good example is to look at how the board of Tesla granted Elon Musk stock options in 2018 that is worth $23 billion!

So back to the example, we now know the option is valued at $5.42x10m = $54.2m. Using the earlier equity value of $1,000, we then subtract $54.2m and divide by 100m shares to finally derive an equity value / share of 945.8/100 = $9.46.

So in summary, this approach sit right in the middle of treasury method and dilution method.

Dilution method @ $9.09 < Value the Option @ $9.46 < Treasury Stock @ $10

How about for future stock options grant?

If the company has been periodically granting options, we can now assume that this is becoming part of a normal compensation scheme, which means will have an effect on value.

Same approach. Common size the value of the options as % of revenue and use this as the basis for future grants. Take note that as revenue grows larger, this % should be lower. Then use this as a line item as part of opex, thus reduce the cashflow and margin each year.

An important blog post by prof on stock-based compensation for further reading.

Storytelling begins! Valuation & narratives.

Every valuation has a story, but numbers and stories should balance each other out.

Narrative drives consistency on the numbers, it provides a hook and make numbers memorable. Conversely, numbers provide stories credibility and gives accountabilities.

Leave on their own device without the balancing act. Numbers can go deep into false precision, being played around too much and lose its meanings. Stories can be fairy tales, misguided by own biases & anecdotes since there are no numbers to prove them.

Step 1: Survey the landscape

Narrative slows down your numbers crunching process. Every valuation starts with a narrative, a story that you want to see unfold in the future of the company.

To develop this narrative, you’ll need to understand the landscape, i.e. the products, the management, the markets, competition & the macro environment it operates.

An example of a company that Prof valued 10 years ago - Uber, in 2013. The trigger for this valuation was when prof read a news in Wall Street Journal that the company raised $17 billion. Prof has never heard of this company before and didn’t know what was ridesharing.

He experimented with it for the first time by taking a trial ride in asking the driver a series of questions like:

Is this the company’s car?

Do you work for Uber?

Why do you want to do this?

How do you get paid, how much?

He also tried paying after the ride was done and was surprised that it was already automatically charge to his card.

The more he finds out by talking with more drivers, the more intrigue and more information he has. At this point, there’s not many financials available.

From the above, he mapped out the following narrative:

Step 2: Create a narrative for the future

They are 3 rules here once you understand the company and the landscape. Your narrative must be:

Simple

Focused and;

Grounded in reality.

Prof’s narrative for Uber back then was the following:

Step 3: Check the narrative against history, first principles & common sense

By using the 3P test of Possible > Plausible > Probable.

This is what separate fairy tales from business stories…

Below are some impossible and implausible assumptions that some of us are guilty of.

// end of Class 12 Valuation